A Pivotal Profession

/FOR OVER 70 YEARS, BOBBY MAY HAS PLAYED A CRITICAL ROLE AS A COURT REPORTER FOR THE JUDICIAL SYSTEM

by LISA PORTERFIELD THOMPSON

photo by Robin Rogers

Bobby May is a legend, in his own right, and the type of rare breed that is not common nowadays. He has been a court reporter for the past 70+ years, and in a society when employees rarely stay with a career until retirement age, that is indeed rare.

“I never thought of any other career I would want to do,” Bobby said. “When I look back on my career, I have no regrets about how I’ve spent it. It’s been a good life.”

Bobby May was born in Celina, Texas, to a cow trader and homemaker. He was the second oldest of four boys and two girls, and graduated from Alla High School. According to him, his father wanted him and his brother to

go in the dairy business, but after hearing a recruiter speak at his country school, Bobby decided to go to court reporting school to avoid milking cows.

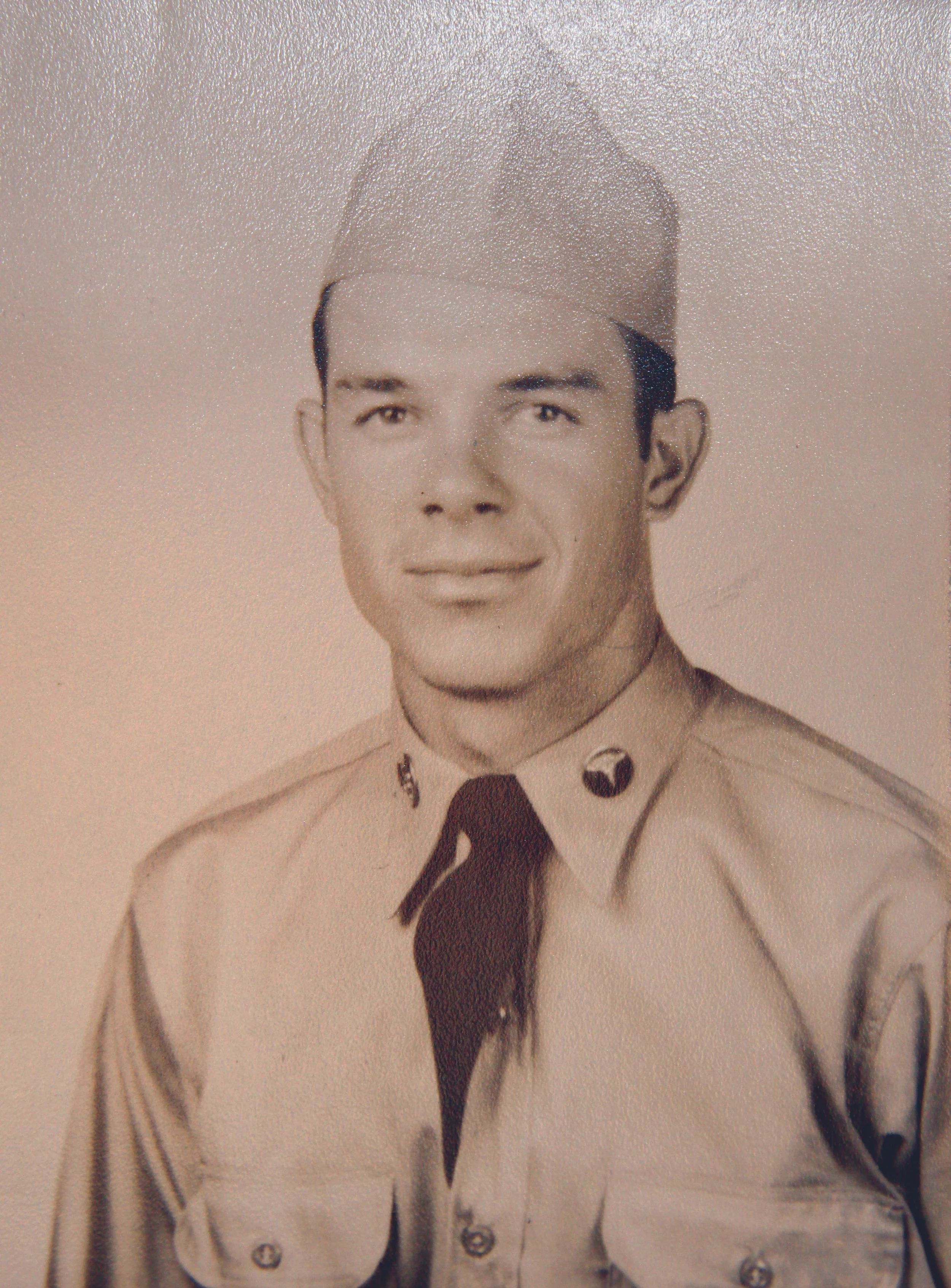

After being drafted into the Korean Conflict, Bobby began working for the JAG office in Japan, reporting court martials.

Bobby’s first job was for a Dallas County Grand Jury beginning on June 1, 1949, earning $250/month. After two years, he married his sweetheart, Mary Jane, a telephone operator for Southwestern Bell, in March of 1951, and was drafted into the U.S. Army in July of the same year.

Because of poor vision in his left eye, Bobby was disqualified from the infantry, but not from the draft altogether. He was trained as a medic, but during his training asked, “Do they shoot at medics?”

“As often as they shoot at the rest of us,” was the reply, and so he elected to go through infantry training and learn weaponry as well as his medic training. After 16 weeks of training, Bobby was shipped to Korea. Upon disembarking the ship, he headed directly for the JAG office and explained that he could be much more help as a court reporter than a medic. The JAG office agreed, and they put him to work as a court reporter the very next day.

Bobby and his wife, Mary, were married during March 1951.

Bobby spent the next 18 months working in Korea. He recalls that some of his most challenging days in the courtroom were recording proceedings there, and one particularly interesting case in which the local Korean officials complained that the United States Army vehicles were all painted a drab olive green color, and it made their city appear as if there were occupying forces.”

“Obviously, there were,” May commented. “But the Korean officials won the case, and the Army painted all the vehicles in the area black. It was one of the most challenging cases I ever reported, because the Koreans’ English was pretty poor, and a lot of their words were out of context. I had a Major come up to me that said he needed the report by the next day. So I took my legal paper notes and manual typewriter back to my office and started transcribing. When my boss showed up for work at 5 a.m. the next morning, I had worked all night, and he was surprised to see me. He took up for me with that other Major, and we sent the report when I was finished with it, but it was not easy work.”

When Bobby was released from the Army, he returned back to Texas and needed a job. He made some phone calls and went to work for a court covering Carthage and Center.

Bobby remembers at the time working for a judge that was 70 years old, and he was 23. “There was a big age disparity,” Bobby explained. “Now, it doesn’t seem like a big deal, but then it was. I was making $4,600/year in 1953, and remember asking him for a raise. He said, ‘Don’t be bugging me with that stuff, I have other things to worry about,’ even though we were riding down the road in my vehicle.”

Bobby shakes his head. “I don’t have anything against anyone working at 70 now.”

Reception Honors Bobby May

On February 21, a reception was held at Northridge Country Club honoring Bobby for his 70+ years of court reporting service. He was also presented a Proclamation announcing the day as Bobby May Day in Texarkana.

(Photos by Mark Patterson, Patterson’s Camera Shop)

Bobby (in the red shirt) with his family members: Matt Combs, Joey Combs, Carrie Slay, Larry May, Jason Combs, Tom Talley, Randy May, Norma May, Jack May, Shedera Combs, Dana Asher, Eloise Talley, Helen Asher, Wesley “Otis” May, Jessie May, Cherie Davis and Marinda Thomas.

Bobby with Texarkana Texas Mayor Bob Bruggeman

from left to right: Bobby with Texarkana Texas Mayor Bob Bruggeman; Darby Doan, representing the Texarkana Bar Association, congratulates Bobby.; The Texas and Arkansas Bar Association’s Louise Tausch shakes hands with Bobby.; Justice Ralph Burgess, from the Texas Court of Appeals, hands Bobby the commemorative plaque.